Flow control and back pressure are critical concepts in building robust, high-performance distributed systems—especially in capital markets, where reliability and efficiency are paramount.

At the recent Aeron MeetUp held in London in June 2025, Mike Barker, a performance engineer working on Aeron, delivered a deep dive into these topics, sharing both theoretical foundations and practical strategies. This blog distills the key findings from his talk, offering a technical overview and highlighting some key techniques on how to deal with back pressure. Watch the full recording for the complete picture, including code samples and real-world scenarios. Watch the full recording here.

What is Flow Control and why does it matter?

Flow control is a mechanism that prevents a fast sender from overwhelming a slower receiver with a distributed system. This is especially relevant in environments where network and memory resources are finite, and where system reliability is non-negotiable.

The key points to consider:

- Flow control is essential for distributed systems to prevent data loss and ensure system stability.

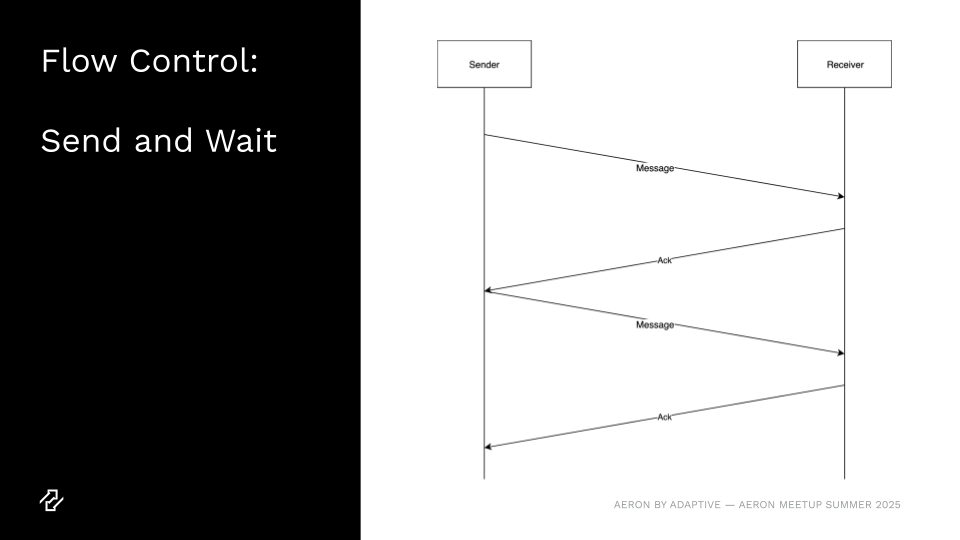

- There are multiple approaches to implementing flow control for a distributed system. The simplest approach is ‘send and wait’, where the sender will wait for an acknowledgement for each message sent.

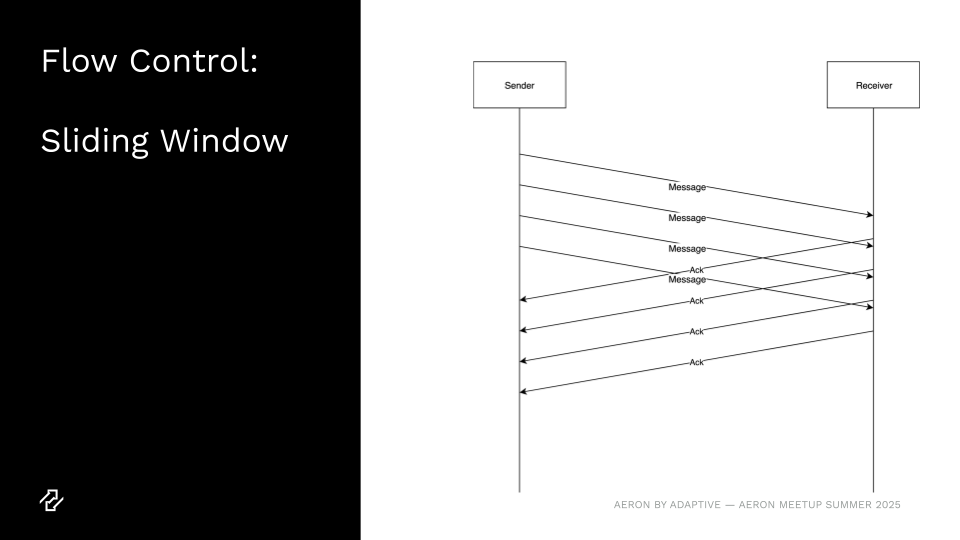

- Transport protocols like TCP and Aeron Transport use a sliding window algorithm that allows more data to be inflight leading to improved network utilisation.

- Many application protocols (e.g., RPC frameworks, HTTP, CORBA) still use “send and wait” models which carry the same inefficiency burdens. High performance distributed systems are better implemented using asynchronous messaging instead of a remote procedure approach.

- Aeron’s implementation stands out by supporting flow control for a single sender distributing data to multiple receivers, which includes configurations using multicast and Multi-destination Cast.

Figure 1.1.: Flow Control – Send and Wait |

Figure 1.2.: Flow Control – Sliding Window |

Understanding Back Pressure & Strategies for Handling Back Pressure

Back pressure occurs when the sender’s window is full and no further progress can be made until the receiver acknowledges the outstanding data, freeing up space in the window. While often seen as a nuisance, Barker emphasized that back pressure is a powerful signal—when handled correctly. It allows for applications to adapt and make smart decisions based on the behaviour of downstream systems.

There are three primary strategies for dealing with back pressure, each suited to different application requirements:

- Abort (drop the message):

- Suitable for scenarios like market data “top of book” updates, where only the latest state matters.

- Highly efficient, but monitoring of dropped data is recommended as it can be an indication of failures elsewhere in the system.

- Fail (notify and escalate):

- Used when message delivery is critical (e.g., order flow in trading systems).

- Notifies upstream systems or users of delivery failure, enabling them to react (e.g., back off or cancel orders).

- Example use case:

Your exchange begins to slow down. Downstream systems are no longer consuming data quickly enough which causes the flow control window to fill up on your input systems and gateways. Eventually, when you attempt to send a new order, you hit back pressure—pushing more messages now only adds to the overload. With the system aware of this state, it can return an error message to external sources, e.g. market makers & traders, allowing them to make their own decisions on what to do when the exchange is in an overloaded state. - Retry (with terminal condition):

- Appropriate when delivery must be attempted multiple times, but not indefinitely.

- Requires a clear termination condition (e.g., timeout, system shutdown, or error state).

- Aeron’s internal mechanisms use idle strategies and timeouts to manage retries cleanly.

- Example use case:

If the cluster gets stuck taking a snapshot due to a disk failure, a standard Java interrupt can be used to break out of the idle strategy and let the system exit cleanly, even if some errors are reported. This provides a well-defined terminal condition for exiting the retry loop, ensuring shutdown is controlled and intentional.

Here are some other best practices tips for handling Back Pressure:

- Avoid excessive logging under high load; use counters or other lightweight observability mechanisms.

- Always define a terminal condition for retries to prevent infinite loops or resource exhaustion.

The solution? Asynchronous APIs and State Machines: Practical Patterns

To avoid the pitfalls of synchronous, blocking communication, the Aeron engineering team developed a task-based asynchronous API for Aeron’s sequencer client. The key features this API design provides:

- Cooperative multitasking (i.e. polling a group of tasks for progress).

- Finite state machines to manage task states (e.g., start, waiting, complete, timeout).

- Unified timeout logic that covers both send and receive operations.

Ready to dive deeper?

This summary only scratches the surface. Watch the full talk recording to see all the code samples and hear the detailed explanations around nuanced trade-offs in flow control design.

Watch the recording to:

- Understand the basic concepts of flow control and how it relates to back-pressure.

- Get an insight in the main strategies for dealing with back pressure within a system.

- See an example of how finite state automata and co-operative multi-tasking can be used as an approach to deal with some cases of back-pressure.